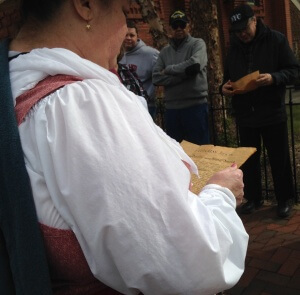

You cannot separate the history of Annapolis from the rich history of the African-American community who made up one-third of the city’s population during the 19th century, and there is no better way to explore that history than taking a walking tour offered by Annapolis Tours by Watermark. Julie Brasch, Mistress Julie as she has been known for the past 15 years, leads people through the cobblestone streets of the city, bringing knowledge and compassion to the stories.

The tour starts at City Dock where 48 slave ships brought human cargo to Annapolis between 1756 to 1775. Mistress Julie told of the journey of Kunta Kinte, an ancestor of Alex Haley (the writer of the award-winning novel and movie, “Roots”), on the Lord Lingonier which docked in Annapolis in 1767. This spot is marked by the Kunta Kinte-Alex Haley monument, the only one of its type in the country, which sits outside the historic Annapolis Market House.

The Market House, which has serviced Annapolis since 1788, was a meeting place for African-American slaves and indentured servants. There they sold eggs, produce, and handmade goods. More importantly, this was one of the few places where fractured families could reunite and discuss the events of the day.

As we passed by historic landmarks throughout the city, Mistress Julie pointed out old taverns behind which slaves were sold. She stressed the sadness of broken families, sold to different masters, and educated us on the local mixing of races (African, Native American, and Irish) that took place during that time. Dressed as an indentured servant, Mistress Julie told us how she personally traces her heritage back to that mixing of lines.

Strolling past brick, cloboard, and wooden style homes, it was uplifting to learn about the first African-American school at 91 East St, which was opened in 1868 by the Order of the Galilean Fisherman. Many African-Americans lived in tenements along East and Fleet streets. Renting these 2 room row houses gave them easy access to their work at the Naval Academy. The first ‘free person of color,” James Holliday, purchased 97, 99, and 101 East Street in 1850, and his decedents still own #99 today.

We ended our two-hour expedition at the Banneker-Douglas Museum on Franklin St. The museum is housed in a nationally registered historic building, which was originally the Mt. Moriah A.M.E. Church built in 1874. The museum was dedicated in 1984, and is the official repository of African-American culture in Maryland.

Informative and humbling, Mistress Julie reminded us that, though we may no longer enslave people today in this country, people are still very judgmental of others and “could be a little kinder.” Thank you Mistress Julie for a wonderful afternoon and your historical knowledge.

Leave A Comment